The vortex flows behind the airfoil creating a downwash that extends back to the trailing edge of the airfoil. This action creates a rotating flow called a tip vortex. The high-pressure area on the bottom of an airfoil pushes around the tip to the low-pressure area on the top. While most of the lift is produced by these two dimensions, a third dimension, the tip of the airfoil also has an aerodynamic effect. To this point, the discussion has centered on the flow across the upper and lower surfaces of an airfoil. Yet, these airfoils do produce lift, and “flow turning” is partly (or fully) responsible for creating lift. A paper airplane, which is simply a flat plate, has a bottom and top exactly the same shape and length. In both examples, the only difference is the relationship of the airfoil with the oncoming airstream (angle). These are seen in high-speed aircraft having symmetrical wings, or on symmetrical rotor blades for many helicopters whose upper and lower surfaces are identical. In fact, many lifting airfoils do not have an upper surface longer than the bottom, as in the case of symmetrical airfoils. The production of lift is much more complex than a simple differential pressure between upper and lower airfoil surfaces. These are seen in high-speed aircraft having symmetrical wings, or on symmetrical rotor blades for many helicopters whose upper and lower surfaces lift is a complex subject. An airplane’s aerodynamic balance and controllability are governed by changes in the CP.Īlthough specific examples can be cited in which each of the principles predict and contribute to the formation of lift, lift is a complex subject. In the design of wing structures, this CP travel is very important, since it affects the position of the air loads imposed on the wing structure in both low and high AOA conditions. At high angles of attack, the CP moves forward, while at low angles of attack the CP moves aft. The average of the pressure variation for any given AOA is referred to as the center of pressure (CP). Figure 3 shows the pressure distribution along an airfoil at three different angles of attack. This negative pressure on the upper surface creates a relatively larger force on the wing than is caused by the positive pressure resulting from the air striking the lower wing surface.

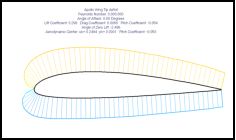

AIRFOIL DESIGN CHARACTERISTICS FULL SIZE

Leading edge (Kreuger) flaps and trailing edge (Fowler) flaps, when extended from the basic wing structure, literally change the airfoil shape into the classic concave form, thereby generating much greater lift during slow flight conditions.įrom experiments conducted on wind tunnel models and on full size airplanes, it has been determined that as air flows along the surface of a wing at different angles of attack (AOA), there are regions along the surface where the pressure is negative, or less than atmospheric, and regions where the pressure is positive, or greater than atmospheric. Advancements in engineering have made it possible for today’s high-speed jets to take advantage of the concave airfoil’s high lift characteristics. As a fixed design, this type of airfoil sacrifices too much speed while producing lift and is not suitable for high-speed flight. The most efficient airfoil for producing the greatest lift is one that has a concave or “scooped out” lower surface.

The weight, speed, and purpose of each aircraft dictate the shape of its airfoil. Many thousands of airfoils have been tested in wind tunnels and in actual flight, but no one airfoil has been found that satisfies every flight requirement. They vary, not only with flight conditions, but also with different wing designs.ĭifferent airfoils have different flight characteristics.

It is neither accurate nor useful to assign specific values to the percentage of lift generated by the upper surface of an airfoil versus that generated by the lower surface.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)